What if the biases and prejudices that are so often wrapped up in languages could be circumvented? Well, that’s exactly what Ludwik Lejzer Zamenhof sought to do by creating Esperanto. Esperanto is a language that was invented by L.L. Zamenhof in 1887.[1] He intended for it to be used as an international auxiliary language. This means basically that Esperanto would serve as a language untethered to any particular country, or ethnicity, making it neutral.

L. L. Zamenhof | Otto Mayer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

When considering the adoption of Esperanto as a universal language, the 1922 Report of the League of Nations articulated this very need in these words: “there is a feeling that it is urgently necessary to escape from the linguistic complications which impede international relations and particularly direct relations between peoples.”[2] This is why the word “Esperanto” literally means “one who hopes”[3] The invention of a language would have been an essential piece of engineering required to make the League of Nations, and many hoped Esperanto would accomplish this.

Esperanto was not adopted as an official language of the League of Nations, with only France opposing the idea.[4] However, the language’s creation still plays an important part in linguistic history, and lives on into the present! Below we will discover Zamenhof’s reasons for inventing Esperanto, some specifics of the language, and finally where it stands in the present time.

The Backstory

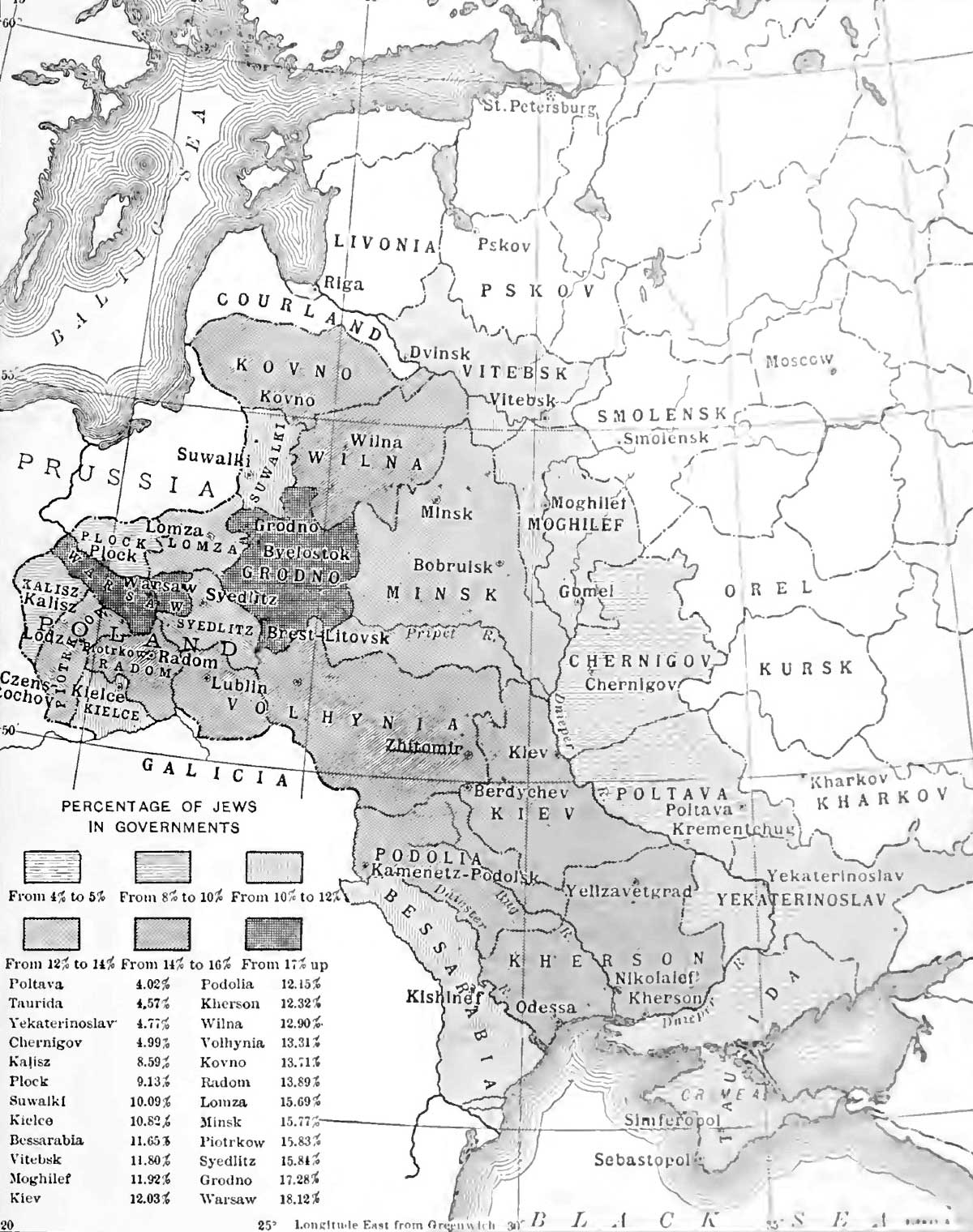

Map showing the percentage of Jews in the Pale of Settlement and Congress Poland, The Jewish Encyclopedia (1905)| Not specified in source., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Before we cover any more details regarding Esperanto as a language, it is important to understand the motivation behind this story of hope. Zamenhof’s particular childhood experience as what he calls a “Jew from the ghetto”, ignited his desire to unite people.[5] Growing up in the city of Belostok, which was then part of the Russian Empire, Zamenhof lived amongst Russians, Poles, Germans and Jews.[6]

From a young age, Zamenhof noticed that the divisions between people which occurred naturally as a result of their nationalities, and languages, caused strife in his city. Zamenhof noted that language in particular was the most prevalent root of this hostility.[7] Luckily, Zamenhof’s particular position at the bottom of social hierarchy gave him an empathetic disposition, driving him to live his life as a herald of authentic selflessness.

Zamenhof expressed these tensions and desires in these words:

No one can feel more strongly than a ghetto Jew the sadness of dissension among peoples …my Jewishness is the main reason why, from my earliest childhood, I gave myself wholly to one overarching idea and dream, that of bringing together in brotherhood all of humanity. That idea is the vital element and the purpose of my whole life. The Esperanto project is merely a part of that idea…(Mi estas Homo 99,100)[8]

Zamenhof accomplished what he believed was the most essential task required to unite people, by engineering Esperanto. His sincere desire to help his fellow human truly was evident in other parts of his life as well. Aside from creating Esperanto, he worked professionally as an ophthalmologist, pacifist, and philosopher.

The Science of Zamenhof’s Observations

It’s no secret that languages truly can divide people the way Zamenhof observed in his own life. Zamenhof’s assessment of the power language has to unite or divide people, may have been informed by his childhood, and the fact that he was a polyglot.[9] However, the honest person can easily recall a time in their life when they witnessed someone being ostracized because of their accent, or language. As time has progressed, several studies have explored the ways we judge others based on the way they speak.

Humans are keenly equipped to audibly determine a person’s ethnicity. A study conducted by linguists Purnell, Idsardi, and Baugh, found that in a phone conversation, people could detect the other person’s ethnicity after hearing their first word, 70% of the time.[10] It almost seems like a superpower that we are capable of discerning someone’s ethnicity so quickly, but as it turns out, it’s simply part of our nature. After all, the development of language is tied inextricably to the development of our species.[11]

This may seem like a superpower, but people often allow differences in speech to translate into negative attitudes. Multiple studies have shown that linguistic biases yield unfavorable results for minorities in legal contexts, housing practices, education systems and hiring processes. [12]

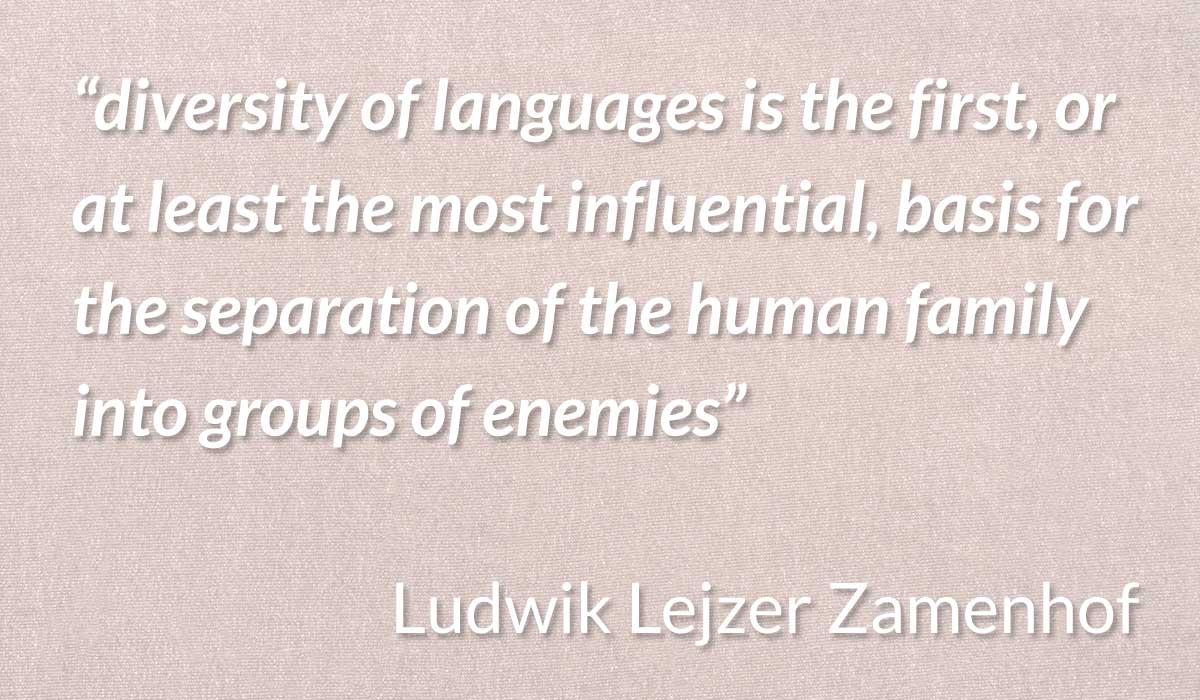

L. Zamenhof observed precisely this phenomenon in a letter to Nikolai Borovko, in 1895, saying: “diversity of languages is the first, or at least the most influential, basis for the separation of the human family into groups of enemies.” In the same letter he went on…“I often said to myself that when I grew up I would certainly destroy this evil.”[13]

Specifics Of Esperanto and Its Usefulness

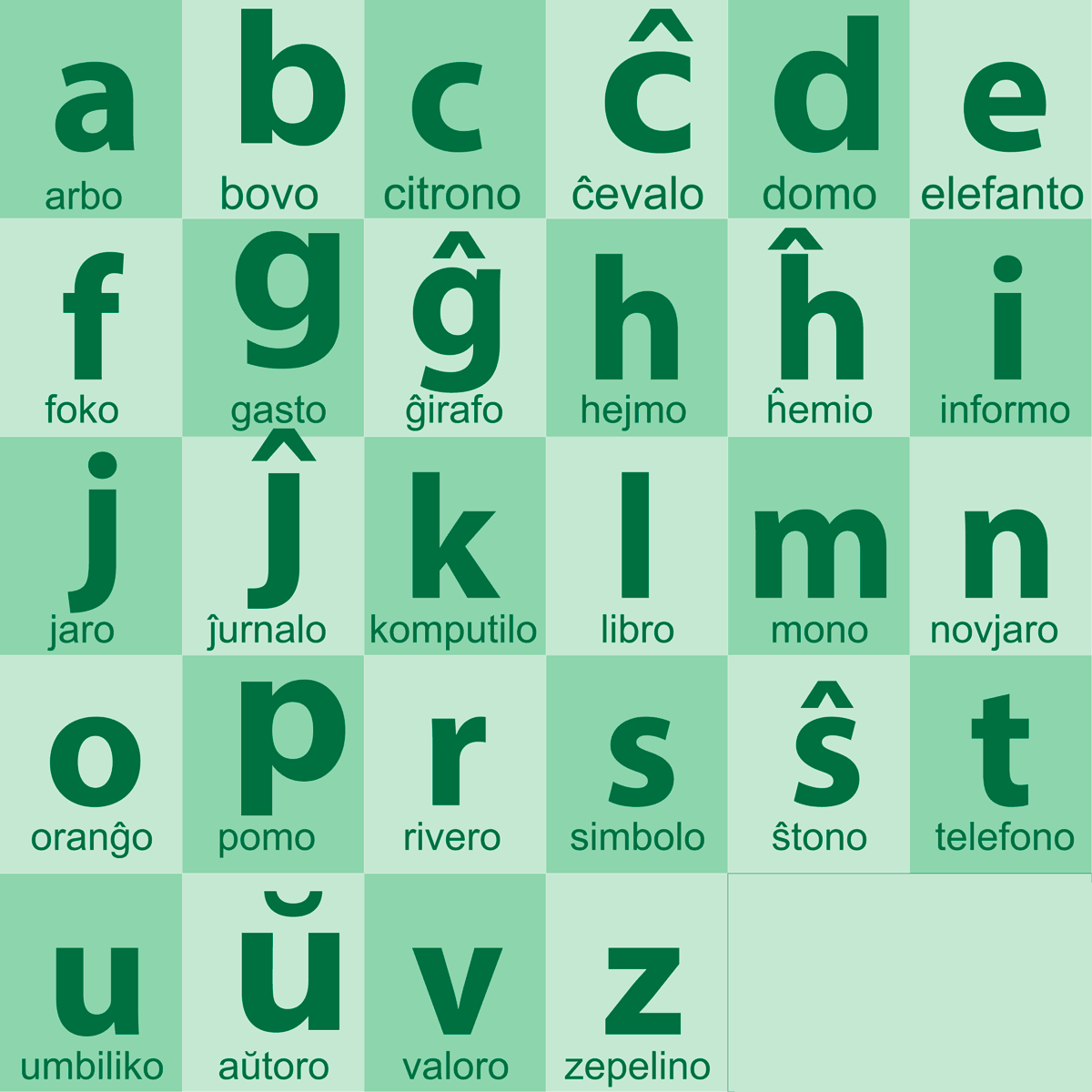

Esperanto Alphabet

Over time, languages evolve through slang, the adoption of loanwords, and decay or changes in meaning. This means that exceptions in rules to grammar, punctuation, spelling and pronunciation arise as time goes forward. Isolated populations often manipulate languages to fit their needs, and as decades and centuries pass, the previous version of a language may be unintelligible to those who now speak it.[14]

As a result, every naturally occurring language in the world has exceptions to its own rules. In English a specific example of this would be the word “deer” for example, which stands for both singular and plural forms of the word. An example in Spanish is the word “sofa” which appears to be feminine because it ends in “a”, despite its being a masculine noun. So, if you were to translate “the sofa” in Spanish, you might mistakenly translate it as “la sofá”, when in reality it is “el sofá”. This list of exceptions could seemingly carry on into eternity.

As noted previously, Esperanto is a synthesized language. It has also been called a constructed language, and an artificial language. Whatever you want to call it, this means that it was created rather than developing naturally over time.[15] This doesn’t mean that the alphabet, sounds or inspiration for words were concocted out of thin air. Well, about 1% of them were. The vocabulary is based on multiple languages, but about 75% of the words are based on Romance languages, with a heavy emphasis on French. Greek accounts for around 13%, English and German together account for around 10%. This leaves a remaining 1%, which is composed of Slavic roots according to scholars.[16]

Esperanto’s alphabet is composed of 28 letters that were taken from the Latin alphabet. The letters always sound the same, all letters are pronounced (meaning there are no silent letters) and the sound a letter is associated with, never fluctuates. By contrast, in English the sound typically associated with the letter “s”, is also associated with the letter “c” sometimes, like in the word “cease”.[17] These are simply more examples of Esperanto’s engineered ease.

The fact that Esperanto was fabricated means it has absolutely no grammatical exceptions. There are never irregular tenses, or prepositions, and the way Esperanto is written, is entirely based on phonetics.[18] Additionally, the way new words in Esperanto are constructed is meant to function like building blocks. An example of this is the way you can build from the word “vend” which means “to sell”. “Vendisto” means “salesperson”, “vendejo” means a “shop” and “vendita” means “sold”. The entire language works this way, allowing a new learner to predict what a word will be after learning to root. The uncompromising and consistent use of affixes allows you to transform a root word into dozens of other words without memorizing new vocabulary.[19] Once you’ve learned the affixes and a few hundred words, you can functionally use Esperanto more quickly than a language full of exceptions.[20]

Why Esperanto Is Useful Now

Esperanto is useful because its simplicity allows people to learn how to learn languages. Many examples have been used to illustrate how learning Esperanto prepares a person to learn additional foreign languages. However, one of the examples that works best, is that of a recorder. The recorder is one of the simplest forms of a woodwind instrument.[21] Now they are often used in schools to familiarize young children with music as a whole. The aim in this, is not to convert hundreds of children into professional recorder players. The aim is to foster the musical intuitions of children by allowing them to gain confidence with a simple instrument. Hopefully then, when they pick up a saxophone, or even a guitar, they believe they can make music and already have some sense as to how it may happen.[22]

The number of people who speak Esperanto is roughly estimated at between one and two million people. [23] The Universal Esperanto Association only has around 5,500 speakers declared, and those speakers are in more than 120 countries. Given the fact that there has never been a global language census, this means there could be even more unknown Esperanto speakers![24]

Additionally there is a service called the Pasporta Servo, which allows Esperanto speakers from all around the world to stay in one another’s homes while traveling, like couch surfing. Due to the fact that Esperanto is presumably easier to learn than other languages, it’s quite easy to make acquaintances who speak Esperanto. Easier at least than two people learning to speak mutually exclusive languages filled with linguistic exceptions.

Zamenhof’s vision was one of unity and hope. Thus, it stands to reason that by finding other Esperanto speakers, the potential to meet truly good individuals at home or abroad is much greater. No matter a person’s age, or how they intend to use Esperanto, Zamenhof’s attempt at actually doing the difficult work to unite humanity, is inspiring. His humanitarian project may not have succeeded in the way that he expected, but it’s still a living language. Besides that, no one knows what the future of Esperanto holds.

- [1] https://www.britannica.com/topic/Esperanto

- [2]Esperanto as an International Auxiliary Language (pg, 13)

- [3] https://theophthalmologist.com/subspecialties/one-language-to-unite-them-all

- [4] https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20180110-the-invented-language-that-found-a-second-life-online

- [5] https://paperzz.com/doc/9350089/zamenhof—esperantic-studies-foundation

- [6]100th anniversary of the death of L. ZAMENHOF, the creator of the Esperanto

- [7] https://paperzz.com/doc/9350089/zamenhof—esperantic-studies-foundation

- [8] https://paperzz.com/doc/9350089/zamenhof—esperantic-studies-foundation

- [9] https://www.historytoday.com/archive/birth-ludwig-zamenhof-creator-esperanto

- [10]Perceptual and phonetic experiments on American English dialect identification. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 18, 10-31.

- [11] https://bmcbiol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12915-017-0405-3

- [12] https://www.unr.edu/nevada-today/blogs/2020/the-sound-of-racial-profiling

- [13] https://twopluscrew.com/2018/09/10/on-learning-esperanto-the-international-language/

- [14] https://www.ling.upenn.edu/courses/Fall_2003/ling001/language_change.html

- [15] https://esperanto.lingolia.com/en/background/what-is-esperanto

- [16] https://culture.pl/en/article/how-much-polish-is-there-in-esperanto

- [17] https://www.blog.coliglote.com/en/2020/12/09/lesperanto-une-langue-bien-vivante/

- [18] https://jakubmarian.com/learning-esperanto-is-it-worth-it/

- [19] https://whistlinginthewind.org/2016/10/24/5-ways-esperanto-is-easier-than-english/

- [20] https://www.fluentin3months.com/2-weeks-of-esperanto/

- [21] https://www.dkfindout.com/us/music-art-and-literature/musical-instruments/recorder/

- [22] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8gSAkUOElsg

- [23] https://www.yayesperanto.com/how-many-people-speak-esperanto/

- [24] https://www.yayesperanto.com/where-is-esperanto-spoken/