Baseball’s Origins

The first time the words “base-ball” are known to have been used in recorded history, was in 1744. The words were used in an English children’s book called A Little Pretty Pocket-Book to describe a game in which 3 boys are standing next to 3 separate posts in a field. One boy is preparing to throw the ball, while another boy is preparing to hit the ball with the palm of his hand. Below the illustration a short verse reads:

“THE Ball once struck off,

Away flies the Boy

To the next destin‘d Post,

And then Home with Joy”[1]

Baseball made its way to the Americas by way of English settlers. In the early part of the 18th century, there were multiple bat and ball games being played in England. Among these were cricket, stool ball, trap ball and again “base ball”. Words discovered to have been hand written in a notebook found in Surrey, England in 1755. All of these games find a common link with stoolball, which dates back to at least the mid-15th century in England.[2]

Between 1861-1865, American baseball took its current form with the advent of meticulous score keeping. By 1871 the United States had its first professional baseball league, and the sport continued to grow in popularity until it exploded in the 1920’s.

History of Baseball in Latin America

What should be obvious by baseball’s history, is the fact that it was developed by English-speaking countries and people but baseball wasn’t only taking root within the continental United States. Simultaneously, the sport was gaining popularity in multiple countries where Spanish was the native language.

Two Cuban brothers, Nemesio and Ernesto Guilló, returned to Cuba after finishing their education at Springfield College in Mobile, Alabama. These brothers exported their love for the game and began teaching other Cubans how to play as early as 1864. This resulted in the formation of the Habana Baseball Club. Similarly, brothers Teodoro and Carlos de Zaldo, returned to Cuba after completing their education at Fordham College in the Bronx, NY, in 1878. Like the Guilló brothers, Teodoro and Carlos created the Almendares Baseball Club, which became the rival of the Habana Baseball Club. This quickly developed into a Cuban league.[3]

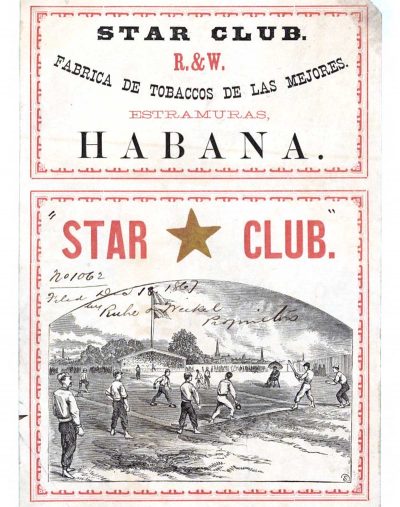

Print of tobacco package label showing a baseball game from the third base side, 1867. [4]

As a result of the Ten Years War between Cuba and Spain, many Cubans fled to the Dominican Republic for safety and brought the game with them. The popularity of baseball quickly grew there with entire leagues being formed there as well.[5] In Mexico, there are debates about baseball possibly having been introduced as early as 1847 by American soldiers fighting the Mexican-American War. Similar accounts of baseball’s dissemination are given regarding Panama and Nicaragua.[6] Like Cuba’s first brush with baseball, Venezuela encountered the sport when students returned home from the United States in the 1890s.[7]

It is impossible to break down the entirety of baseball’s proliferation through Latin America here. It is clear however that baseball was being played in many Latin American countries by the turn of the 20th century. This is simply due to the United States’ proximity with those countries as a result of war, education, commerce and more. One thing should be obvious, baseball’s history does not belong solely to the United States. In fact, the United States has depended on Latin American talent for decades, and does even today. It is quite common today for Major League teams to recruit players not only from the Dominican Republic, but also Venezuela, Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Cuba. [8]

Hardships For Latin American Players in the United States

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Estevan Enrique “Steve” Bellán, from Cuba, bridged the professional gap between Latin America and the U.S. As the first player from Latin America to participate in professional leagues in the United States he played in the U.S. major leagues from 1868 to 1873.[9] After this stint in the U.S., he returned to Cuba to help cultivate and organize baseball there.

Word spread of Cuba’s growing talent, and much in the same way that Cuba was the first Latin American country to adopt baseball, Cuba was the first country visited by a Major U.S. team. In 1908 the Cincinnati Reds held a 5 game match against Cuba’s Almendares club on Cuban soil. The Cubans beat the Reds in 4 out of 5 games.[10]

Ignoring the simple merit of a player’s abilities, major league baseball was still a relatively new phenomenon and the “color line” barring people with darker skin from playing, was drawn early in baseball history. It’s difficult to document the beginning of this separation because the color line was a tacit rule.[11] Even so, there is evidence that racial divide has origins as early as 1883.[12]

From 1900 to 1950, only 53 Latin American players were signed to major U.S. teams.The decision about whether or not these men could play was usually based upon how dark their skin was. If a player could pass as white, they would be allowed to join a team. Otherwise, they were relegated to summer teams, or minor leagues.

In these minor leagues, Latino players would often be forced to play in small cities throughout the United States with no Spanish-speaking community. These players were separated as they were signed to different teams, keeping them from one another in unfamiliar, white communities. This multiplied the difficulty of everyday life for Spanish-speaking baseball players who had to struggle through basic activities like ordering food and getting directions.[13]

This continued into the 1960s and 70s, when Latin American players came from Puerto Rico rather than Cuba. By the 1980s, the Latin American country providing the most players switched decisively to the Dominican Republic.[14] This trend still rings true in the present with 10% of all major league players coming from the Dominican Republic in 2021.

The discrimination against Latino baseball players is not confined simply to their skin color, or native language. While the minimum salary of a major league player was $84,000 a month as recently as 2014, the minimum monthly salary for a minor leaguer was $1,100. The practice of relegating Latino players to the minor leagues in the United States means then, that they are underpaid for their skills while they await a major league contract with often unrealized hope.[15]

Speaking Spanish in Major League Baseball

Given the number of Spanish Speaking baseball players that have contributed to Major League Baseball for the better part of an entire century, it’s incredible how little headway has been made in the department of bilingualism. Of course there have been some noteworthy Spanish game announcers such as Buck Canel, and Jaime Jarrin. Yet, there have only been three Spanish-language broadcasters inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. This lack of priority of the Spanish language was reflected in the Dodgers’ decision to create bobblehead dolls of the 10 Dodger greats. The organization did not include Jaime Jarrin in the lineup despite his service to the Dodgers for 60 years until they were pressured by bad publicity.[16]

An interview conducted in 2020 by Jesse Sanchez, a national reporter for MLB.com, featured professional baseball players from multiple Spanish-speaking countries as a first annual roundtable discussion celebrating Hispanic Heritage month. These players discuss what life is like for them as Latinos in the U.S. Throughout the interview it becomes obvious that despite the discrimination and difficulty for Latino players, these men describe their experience with gratitude and perceive their career in baseball as miraculous.

When Jesse Sanchez asked how important it was for these players to learn English they shared their multiple perspectives. Fernando Tatis Jr. from the Dominican Republic says “As fast as we can learn English, it will be way better”, citing the need to socialize with people in the U.S., so as to be understood fully as a person. Francisco Lindor from Puerto Rico describes his primary motivations for learning English as simply being able to order food and describe when a part of his body was in pain. Johan Santana from Venezuela relays the importance of speaking English, saying “… to communicate and interact with people was one of the toughest things, and yet was the key for me to put myself into it, trying to get better not just as a baseball player, but as a human being as well.”

Mariano Rivera from Panama recalls particularly emotional memories as a young player in North Carolina where no one spoke Spanish. He says “I used to cry, not because of the game, I used to cry because I couldn’t communicate. It was the most horrible feeling that I ever experienced because you can’t express yourself.” Mariano goes on to say “I didn’t go to school to learn English, I learned English through baseball.”

Jesse Sanches goes on to ask these players, “how important is it to reach out to all the fans in both languages?” Francisco Lindor emphatically replies “I think it’s huge, it’s extremely important to be able to interact and engage with Latin-speaking people and Americans speaking English.” He goes on to add “I take great pride in being able to talk and communicate and let people know that we’re humans… you know you see us on T.V., you might think you know our lives but we’re humans, we make mistakes, we have emotions…”[17]

With the discrimination and hardships for Spanish-speaking baseball players in mind, it’s important to recognize that there may be some light in the game’s future. In 2020, 21 different major league players have chosen to feature the Puerto Rican singer, Bad Bunny’s music as their walk-up song.[18] Additionally, the “Ponle Acento” campaign, meaning “put the accent on it”, was launched in 2016. This campaign finally ensures that Latino player jerseys are embroidered with the proper accent marks to accompany letters in their names.[19]

There are still systems in place within major and minor league baseball that exploit Latino players, but progress has certainly been made. Through Spanish-speaking sports announcers, walk up songs, and accent marks on jerseys, baseball is slowly coming into its true bilingual identity. The past and present of baseball relies heavily on Spanish-speaking nations and people to survive. So, the importance of allowing these players and their communities at home to express themselves as Spanish-speaking people, recognizes them not just as talented players, but as humans.

- [1]http://static1.1.sqspcdn.com/static/f/132778/24206174/1389711482663/pretty+little+pocket+book.pdf

- [2]https://edition.cnn.com/2010/SPORT/06/01/lords.museum.baseball.cricket/index.html.

- [3] https://www.britannica.com/topic/Latin-Americans-in-Major-League-Baseball-910675

- [4] http://loc.gov/pictures/resource/ppmsca.17527/

- [5] https://jaimebonettizeller.com/history-baseball-dominican-republic/

- [6] http://metsminors.net/baseball-history-in-latin-america-mexico/

- [7] https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/History_of_baseball_in_Venezuela

- [8] https://www.baseballamerica.com/stories/which-countries-produce-the-most-mlb-players/

- [9] https://uproxx.com/sports/latinos-history-basesball-roberto-clemente/

- [10] https://uproxx.com/sports/latinos-history-basesball-roberto-clemente/

- [11]https://journals.uair.arizona.edu/index.php/azjis/article/download/18591/18233

- [12] https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/august-10-1883-cap-anson-vs-fleet-walker/

- [13] http://websites.umich.edu/~ac213/student_projects05/ls/barriers.html

- [14] https://digital.sandiego.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1010&context=theses

- [15] https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/does-major-league-baseball-exploit-latino-players-n228316

- [16] https://www.latimes.com/sports/la-sp-jaime-jarrin-plaschke-20180324-story.html

- [17] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eTuf8-YXbtg&t=206s

- [18] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I61Qbc9HX-4

- [19] https://tht.fangraphs.com/mlbs-ponle-acento-campaign-is-a-step-in-the-right-direction/