Humanity has always needed to communicate cross-culturally. This need is often motivated by scientific research, commerce, political negotiations, or the translation of religious texts. Yet, the different languages of the Earth have always posed potential problems for mistranslation. There are times when these mistranslations have inconsequential results, and there are times when these mistranslations have nearly catastrophic results.

Here, we will look at three times in history when mistranslations had palpable consequences. We will treat these three occurrences from least consequential, to most.

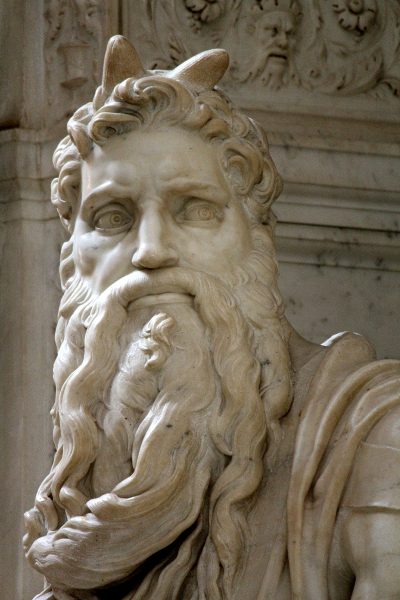

Moses and His Horns

Moses by Michelangelo (Detail)

If you visit St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, you might see a statue of Moses which dates back to somewhere between 1513-1515. The statue was sculpted by Michelangelo, and features Moses with the Ten Commandments, a stern expression, and horns emerging from his head.[1] Yes, horns. In fact, it is not only Michelangelo’s depiction of Moses which gives him horns. It was fairly common during the renaissance for Moses to be shown with Horns.[2]

Michelangelo by Daniele da Volterra

The origin of the misconception comes from Exodus 34:29. In this passage, Moses had just returned from his encounter with Yahweh on Mt. Siani and the skin on his face “qaran-ed.” “Qaran”, is a transliteration of the Hebrew word “קָרַן”, and has two possible meanings. The first meaning is “to send out rays” and the second is “to display or grow horns.”[3] This might feel bizarre at first, but remember that English is filled with homographs. That is, words with the same spelling but two different meanings.[4] One example is bear, which can mean “to hold up”, and also refers to the mammal.[5]

Thus, two translations of the Hebrew Bible dealt with the issue of how to translate the word “qaran” into their respective languages. These are the Aquila and the Vulgate. The Aquila is a 2nd century C.E., Greek translation and the Vulgate is a 4th century C.E., Latin translation. Both translations decided on translating the word “qaran” as “horned”.

It may seem obvious now that the Bible did not intend to describe Moses as having horns emerging from his face. However, in the Bible, the only other time the Hebrew word “קָרַן”, is used as a verb, is in Psalm 69:31. In this case, the word is in fact describing “a bull with horns and hoofs.”[6] It is not unreasonable then that the Aquila, and the Vulgate would translate this word as “horned”. Based on Psalm 69, which was much more clear in its use of the word “qaran” as a verb, describing Moses as having horns was an attempt to be faithful to the text.[7] It is worth noting additionally, certain Gods of the Ancient Near East were often portrayed as having horns.[8]

The Aquila and the Vulgate then, were not translated by madmen. Instead, we might understand the mistranslation of “qaran” as “horned”, to be the result of an overzealous attempt to be true to the Biblical text. Either way, “to shine” is now accepted as the correct translation of the verse.[9] While the hundreds of depictions of Moses with horns may give you a laugh, at least they do not strike fear in your heart. The same cannot be said for our next mistranslation.

Intelligent Life On Mars

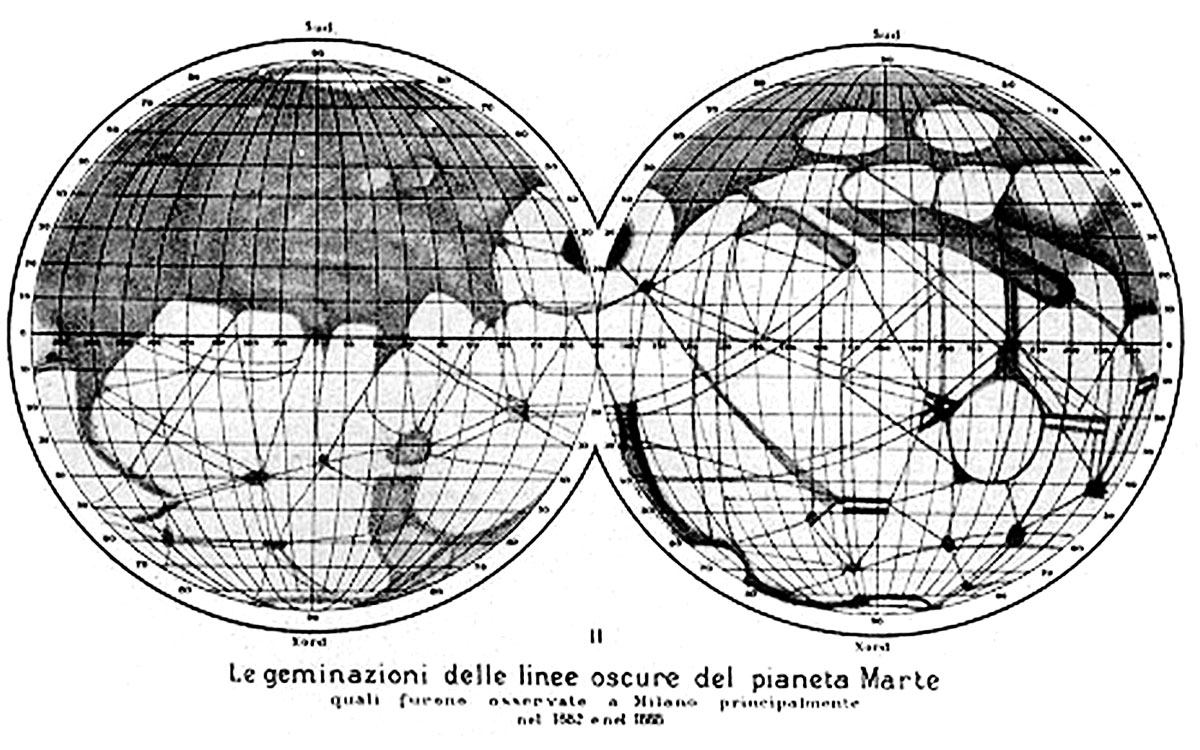

Mars twin canals by Schiaparelli

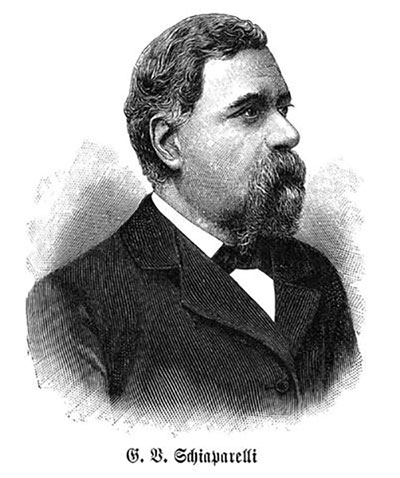

In the second half of the 19th century, Giovanni Schiaparelli became one of the world’s most widely trusted astronomers.[10] This was partially due to Schiaparelli’s use of a very powerful instrument, the 22 cm diameter Merz telescope. This telescope replaced earlier telescopes in the Brera observatory in Milan, which were around one century old.[11] In 1877, Mars passed very near to the Earth. This proximity, combined with the new Merz telescope, gave Schiaparelli a unique opportunity to observe Mars.[12]

Giovanni Schiaparelli

Upon observation of Mars, Schiaparelli drew maps of the planet exhibiting long, straight lines which ran across its surface. Schiaparelli described this network of lines as “canali” in Italian. The Italian word actually means “channel”, in English, but was mistranslated as “canal”.[13] The word “canal” implies with almost all of its possible definitions, that it is artificially created.[14] It is important here to note the recent completion of the Suez Canal in 1869. This engineering feat amplified the importance of human-made canals in popular imagination.[15]

At the time, Schiaparelli’s drawings were believed to be the most authoritative because he had some of the best equipment, and his drawings were more precise than other maps that had been rendered.[16] Schiaparelli’s authority, coupled with new faith in a species’ ability to construct large scale canals, ignited the imagination of Percival Lowell when he read the mistranslated “canal”, in 1895.[17]

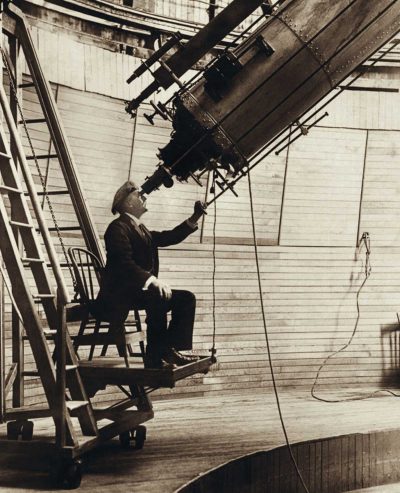

Percival Lowell – Observatory

Lowell was a wealthy astronomer from Boston, enabling him to construct a private observatory in Flagstaff Arizona. Using this observatory, he devoted himself to studying the surface of Mars. Lowell took the mistranslation to another level, determining that the “canals” had been constructed by intelligent life on Mars to irrigate the planet. Lowell went so far as to publish a book titled Mars and Its Canals.[18]

Mars and its Canals- AIP American Institute of Physics

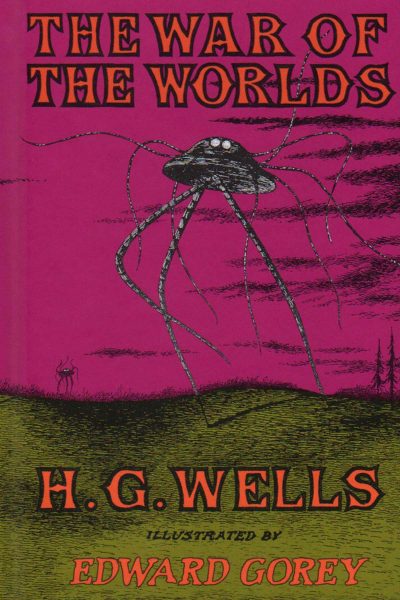

This mistranslation and subsequent false evidence, bled into the imagination of H.G. Wells, who published The War of the Worlds, in 1898.[19] The premise of which was that intelligent beings from Mars invaded Earth, assuming control of it with violent force.[20] In 1938 Lowell’s mistranslation of “canali”, and Well’s The War of the Worlds finally culminated with real-world consequences when Orson Welles broadcast an updated version of Well’s novel as a radio show. The radio show was presented as fiction, however, the American public misunderstood and believed they were listening to a real time news report of an alien invasion.[21] The radio show sounded extremely realistic and sent thousands of Americans into a panic.

The War of the Worlds – H.G. Wells (Book Cover)

We can trace a line of influence from Schiaparelli observations to Orson Welles’ panic-inducing radio broadcast. Lowell’s mistranslation of Schiaparelli’s “canali” into “canal”, animated Lowell’s eager imagination, causing him to believe there was intelligent life on Mars. H.G. Wells was then influenced by Lowell resulting in his novel The War of the Worlds. This eventually led to Orson Welles radio broadcast, which even had to be investigated by the Federal Communications Commission, but was ultimately deemed unmalicious.[22]

New York Times – The War of the Worlds – Headline from October 31, 1938

Essentially, it can be argued that if “Canali” had simply been translated as “channels” rather than “canals”, none of this would have taken place.

The Young Assassin George Washington

Washington and Capt. Jacques St. Pierre

Another mistranslation had more tangible consequences than the seeming near-brush the U.S. had with Martians. This mistranslation took place between a young George Washington and French forces in the Ohio River Valley.

The background information is as follows: in the mid 18th century, the French owned much of Canada and the Louisiana territory, and wanted to control the massive area between the two. By 1754 the French were building forts north of Ohio, and slowly heading in that direction. At the same time, the Ohio Company of Virginia wanted American families to settle in the Ohio River Valley and eventually move west. The French understood this movement of settlers as an intentional wedge between their two territories.

George Washington Portrait by Charles Wilson Peale

In addition to the struggle for power between French forces and British/American forces, there was tension between native Americans who had sided with the French and native Americans who had sided with the British.[23]

As of yet, George Washington had never personally engaged in combat and was taking his battle cues from an Iroquois warrior named Tanacharison, who was also known as the “Half King”.[24] On May 28, 1754, after what Washington himself described as a “march through heavy rain” in the darkness of night, he and Tanacharison surrounded French soldiers in a ravine around 7 am. Most likely due to Washington’s inexperience, he was accidentally seen by the French which caused panic and ultimately gunfire ensued. It was said that it was nearly impossible to tell who fired first.

Tanacharison painting

The French were trapped with British soldiers on one side, and Iroquois warriors on the other, motivating their decision to surrender.[25] However, before Washington could officially accept their surrender, Tanaghrisson approached a French Ensign named Jumonville and “struck him repeatedly in the head with a hatchet.”[26] An outlying French soldier managed to escape the battle and report the death of Jumonville and 9 other French soldiers, to French forces on the Ohio River. [27] The French then accused Washington of having led an unprovoked attack on the French.[28] In response, the French led a retaliatory attack on July 3. Washington and his soldiers were outnumbered, causing them to surrender by nightfall.[29]

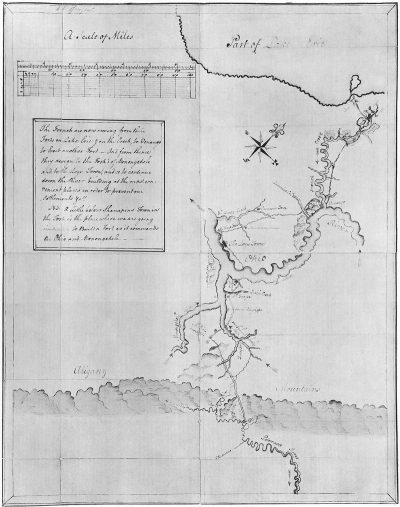

Map of the upper Ohio River and surrounding area drawn by Washington during or after his 1753 expedition

This is where the mistranslation comes into play. Like Washinton’s soaked march through the night on May 28th, this battle had taken place in what Washington called “the most tremendous rain that can be conceived”.[30] The French offered terms of surrender to Washington, which he demanded be in writing. However, it was raining so hard that the French terms of surrender could not be easily read.

Van Braam was one of Washington’s few French speaking soldiers. Only Van Braam could make sense of the terms because he had heard them from the mouth of a French officer. Van Braam was Dutch, so neither French nor English were his native languages. Interpreting as he went along, Van Braam fumbled through Article 7 of the capitulation. The Article in question begins “And as the English have in their Power, one Officer, two Cadets, and most of the Prisoners made at the Assassination of M. de Jumonville…”[31]

Jacob Pieter van Braam by Mathias de Sallieth

However, Van Braam, most likely translating from French, to Dutch, then to English in torrential rain, probably mistranslated “assassinate” as some other word like “kill”, or “attack”.[32] Washington signed the terms and unbeknownst to him, took responsibility for “assassinating” Jumonville.[33] Washington, unknowingly admitted in writing that he had attacked France, when Britain and France were not at war. France took this as an opportunity for propaganda. As mentioned before, France was already motivated by their desire to control the North American continent. Thus, it has been argued that this mistranslation provided fuel for the spark that would eventually lead to the French and Indian War.[34]

Whether it be rain, or preexisting political tensions, the mistranslation of “assassinate”, arguably caused the French and Indian War. If it was not directly its cause, the accidental admission of responsibility on Washington’s part, certainly helped start the war.

In each of these three examples there seems to be a common theme. That is, that the mistranslations are aided by other contextual nuances, and what seems like wilful, or at least imaginative disregard for reality. These three cases doubtlessly live amongst a plethora of mistranslations that have echoed through history. One undeniable lesson emerges from these stories. It is always important to have a good translator.

- [1] https://www.rome.info/michelangelo/moses/

- [2] https://widowcranky.com/2018/06/27/moses-michelangelo/

- [3] https://www.blueletterbible.org/lexicon/h7160/kjv/wlc/0-1/

- [4] https://www.dictionary.com/browse/homograph

- [5] https://www.dictionary.com/browse/bear

- [6] https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Psalm%2069%3A31&version=NRSV

- [7] https://www.thetorah.com/article/moses-shining-or-horned-face

- [8] https://www.thetorah.com/article/moses-shining-or-horned-face

- [9] https://www.jstor.org/stable/26424475

- [10]https://artsandculture.google.com/exhibit/a-new-kingdom-for-astronomy-giovanni-virginio-schiaparelli-museo-nazionale-della-scienza-e-della-tecnologia-leonardo-da-vinci/iwJiupptVgKdJA?hl=en

- [11]https://artsandculture.google.com/exhibit/broadening-perspectives-museo-nazionale-della-scienza-e-della-tecnologia-leonardo-da-vinci/MAJCaX6wZY3yLg?hl=en

- [12] https://www.lindahall.org/giovanni-schiaparelli/

- [13] http://scihi.org/giovanni-schiaparelli-martian-canals/

- [14] https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/canal

- [15] https://www.nasa.gov/audience/forstudents/postsecondary/features/F_Canali_and_First_Martians.html

- [16]https://www.loc.gov/collections/finding-our-place-in-the-cosmos-with-carl-sagan/articles-and-essays/life-on-other-worlds/seeing-and-interpreting-martian-oceans-and-canals

- [17] https://www.nasa.gov/audience/forstudents/postsecondary/features/F_Canali_and_First_Martians.html

- [18] https://www.britannica.com/biography/Percival-Lowell

- [19] https://www.nasa.gov/audience/forstudents/postsecondary/features/F_Canali_and_First_Martians.html

- [20] https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/8909.The_War_of_the_Worlds

- [21] https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/welles-scares-nation

- [22] https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/welles-scares-nation

- [23] http://npshistory.com/handbooks/historical/fone/handbook-1975.pdf

- [24] https://www.history.com/news/george-washington-french-indian-war-jumonville

- [25] http://npshistory.com/handbooks/historical/fone/handbook-1975.pdf

- [26] https://warontherocks.com/2015/10/george-washington-confessed-assassin/

- [27] http://npshistory.com/handbooks/historical/fone/handbook-1975.pdf

- [28] https://www.history.com/news/george-washington-french-indian-war-jumonville

- [29] https://warontherocks.com/2015/10/george-washington-confessed-assassin/

- [30] http://npshistory.com/handbooks/historical/fone/handbook-1975.pdf

- [31]https://founders.archives.gov/?q=%20assassination%20Author%3A%22Washington%2C%20George%22&s=1111311111&sa=&r=1&sr=

- [32] http://npshistory.com/handbooks/historical/fone/handbook-1975.pdf

- [33] https://www.history.com/news/george-washington-french-indian-war-jumonville

- [34] https://www.nps.gov/fone/learn/historyculture/index.htm